I’m pleased to share, with the kind permission of Byline Times, the piece I wrote last December, which appeared only in their paper edition, ‘Who Needs Fame’. It’s a pleasure to report that Byline understood my position on access, so here is the piece digitally, that everyone can hopefully enjoy it.

—————

Eight years old, and I wanted to be a famous astronaut, after seeing the moon landing in 1969. The final stanza in my poem Lost in Spaces says it all:

I’m rolling through the once-sealed door

And floating in a most unexpected way.

Planet Pen evolves, a universe to explore,

And yes. There’s everything to say.

Two years later, around the age of 10, I won a poetry prize at school. Teachers dazzled me by telling me how good I was. Bastards, I say, with hindsight – now I had the bug. The die was cast, and all I could think of was being a famous writer. Alongside, as I grew up, realising on instinct how stupid people were about disability. If only they stopped putting so many steps in buildings. Neil Armstrong, arguably the most famous man in the world at that time, might’ve made one small step, but I was lucky to find a space where I could make my way anywhere.

Punk changed how I saw the world, and provoked the idea that working class kids could make their own version of fame. My journey started in fanzines, where it seemed easy to get things published, at last. Then, as my political awareness evolved, I formed a band. Writing now included protest lyrics, and went hand-in-hand with craving fame. But why would I need it? Because, as someone in a community of the completely unheard, I wanted to be heard.

Who was there to look up to, for me, as a young disabled woman? Where were our role models, disabled role models? This was way before I knew who Frida Kahlo was, let alone that she was disabled. Ian Dury was the first famous person I truly recognised as disabled, who referred to it in his songs, the pinnacle of which, to many activists, was the (quickly banned) Spasticus Autisticus - what an anthem! Obviously, I knew about blind Stevie Wonder, and had also been nagged throughout my childhood about British entertainer Des O’Connor recovering from childhood rickets and injury trauma (he was in an iron lung for six months).

‘If he can get better, so can you!’ I was admonished.

Once I was politicised as a disabled person – becoming a feminist, surviving Thatcher’s Britain, I linked with others through fanzines, punk and the post-punk ethic of DIY indie music. Quickly realising my words had power, which also upped my need to play the game with fame. The ‘80s picked up on the Andy Warhol (misattributed) promise of everyone having ‘15 mins of fame’. The story behind this is funny in itself, with several individuals claiming the phrase. The notion of a brief blaze of fame could even be taken as far back as Elizabethan England, and Shakespearean actor William Kempe’s book Nine Days’ Wonder, leading to the definition (according to Cambridge Dictionary) ‘a cause of great excitement or interest for a short time but then quickly forgotten’. I doubt I am the first to wonder if this is what led to the darker idea of celebrity for its own sake, and today’s fame-without-substance social media influencers.

Back to me, without fame. It’s hard to be famous when you’re a working class disabled woman – in the ‘80s it was impossible. For many years, many people in my close circle worked hard to help me, and I often tagged the odd ‘celebrity’ along the way, but at least these individuals were respected in their fields. These included iconic musician Robert Wyatt (who compared me to Poly Styrene and Jean Rhys). Close associates know about my brief two-way correspondence with old Marmite man himself, Morrissey. Emotionally, this took me to a high and also instilled hope. Back at that time, to have your hero say ‘you write delightfully, a priceless gift’ kept me going for the next few years.

On the back of this, writing, singing and recording as a young disabled woman, I soon met other disabled people within our burgeoning activist movement. My creative endeavours were a new step up in the bid for fame – to get across the disability voice. I recorded an album, and my links to the North London post-punk music scene continue in various forms, with various people, to this day. Such exciting times, and one memory I treasure is I did not detect any sense of prejudice towards me as a disabled woman. These friends loved my work, my words, my songs – my manager even became my boyfriend. He also believed I should be famous, because of what I created.

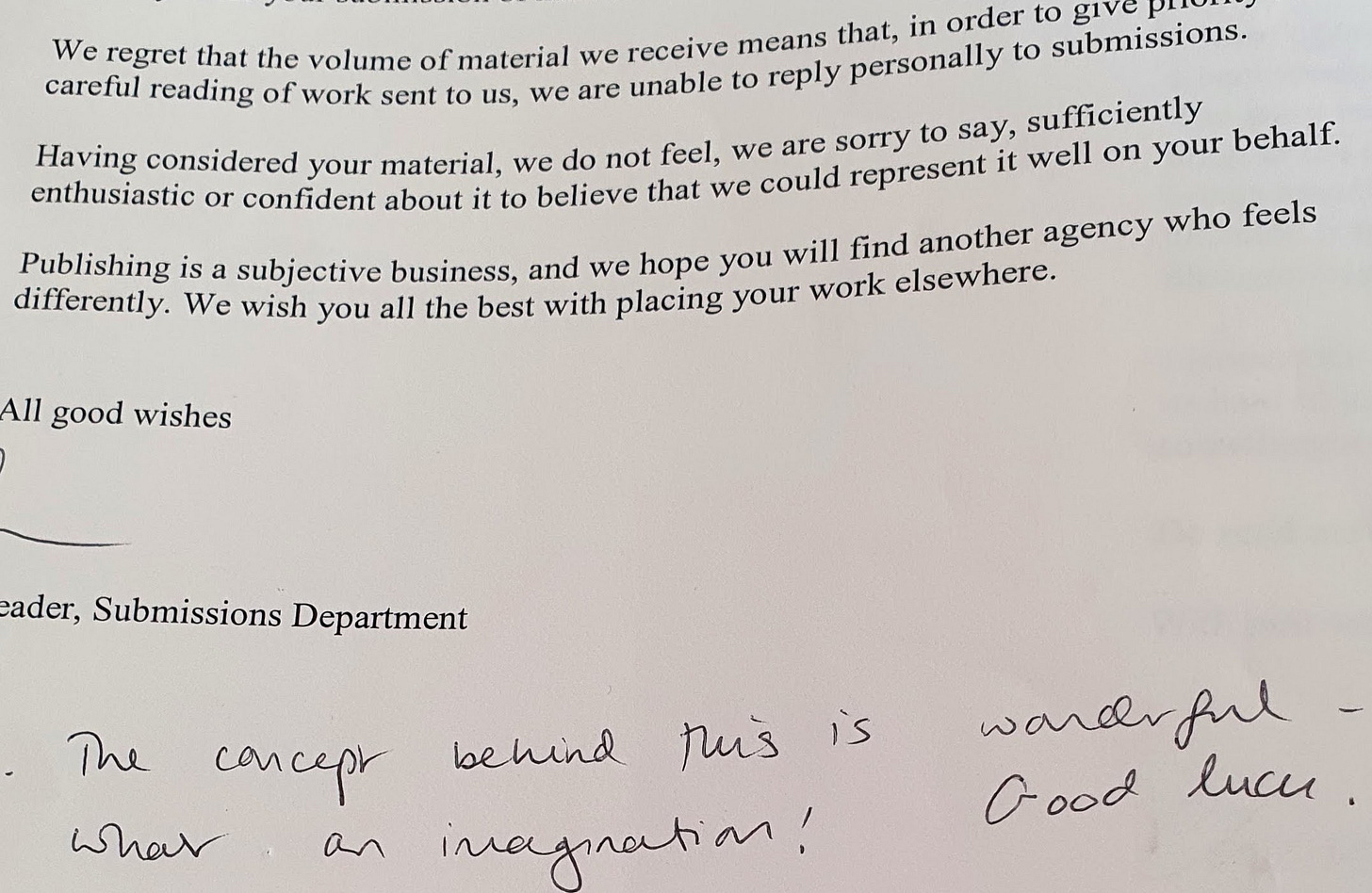

But it was a hard time, because no matter who came forward in support and respect, it still didn’t happen. From then on, I’ve stayed on the fringes, wanting fame within that context of exploring something that’s almost my tagline: ‘telling the untold’. Individuals have continued to help me, seeing power and promise in my writing. But others – including the faceless beast of mainstream publishing – remain disinterested to the point of bland prejudice. ‘Who would want to read my work?’, they’ve said from the early-‘90s onwards, as I wrote and wrote. ‘Stories about the handicapped are negative – that won’t make you famous, or us money.’

Creative organisations helped. It’s how I came to publish the ACE-supported Desires in 2003. My PR for that project was Tony Cowell, brother of, yes, Simon Cowell. What an eye-opener that was in the pursuit of fame. Tony was a kind and colourful individual. He believed in me, and I’m sure he really thought that Desires would take off.

But I knew it was over after he came very close to getting me onto Channel 4, on Richard and Judy’s bookclub segment. Back room TV researchers persisted, and made the right noises about having me on as a guest – as they always do – but then my stories about sex and disability clearly scared them away. Nothing happened, and the unsold copies from that print run are still in my cupboard. The new anniversary edition, Desires Reborn (published as a KPD last March), is available here.

There is a small truth that I’m probably more ‘famous’ within my tiny pool than I realise. Even today, as I write this piece, I Googled ‘disabled woman writer UK’ – guess who came second? Yours truly. Though, occasionally, I come first, and hang around up there with other writers, particularly journalists.

Disability commentators talk about how there are now more famous disabled individuals than ever – but their profile seldom lasts, or keeps a genuine agency beyond a certain flowering, as we all struggle to break away from the tropes and stereotypes imposed upon us. We can forever talk about disability, impairment, the lives we live (or don’t), but are never allowed to flourish as three-dimensional, good-bad, complex, creative beings. Few of us are allowed to be famous in our own right, on our own terms. This was one reason I resisted writing a memoir until my 50s. I wanted it to be less a journey through my impairment (a boring dead end for a writer), and more about my own personal evolution as a creative individual against the backdrop of a disabling society. I will always love Unbound for publishing First in the World Somewhere, and I still have hopes for a paperback edition and a TV adaptation. There was serious interest, and a lot of work in development, but… that’s another story.

Sometimes I forget how close I’ve come to the elusive phantom, fame. And I don’t want fame per se, I want what fame might give me: an elevated voice, to promote social change and tell the disability story. Nick Drake sang, ‘Fame is but a fruit tree, so very unsound’, but whether 15 minutes, or 15 years, I still want it – not empty, not pointless, not for its own sake – but because so much remains untold. And if fame gets me that space, I’ll never give up on chasing it.

Onward and upward. Should be a banner in your bedroom so you can see it every morning when you open your eyes.

I read the print version in Waitrose :] Inspiring, honest and poignant. Might see you Saturday?